|

Preamble

To evoke

the immense history of the Paris quarries, this site offers to bring together

the three main themes of this subeteranean adventure.

The first

file will of course be dedicated to the

underground quarries

themselves, mainly used for

limestone

and gypsum exploitation and later on turned into mushroom farms producing the

famous petit blanc of Paris

Our second file will show all the aspects of

the quarries inspection service

(Inspection des

Carrières), from 1777 to

the present day to detail its

history,

missions and

consolidation methods.

We will finally get onto the last file

dedicated to the quarries by burying ourselves into the history of the

catacombs

and by following a

complete guided tour

of the Paris municipal ossuary

(Ossuaire Municipal de Paris)

Enjoy

the explographies…

Quarries of Paris

Quarries

Exploitation

Since

the time when our civilizations started to build lasting constructions, building

stone has been exploited. Be it for shrines, temples or housing, the stone is a

richness for him who exploits it, no matter what its kind is depending on the

local resources: Granite, sandstone, marble, chalk... and in the region that

particularly interests us :

Limestone.

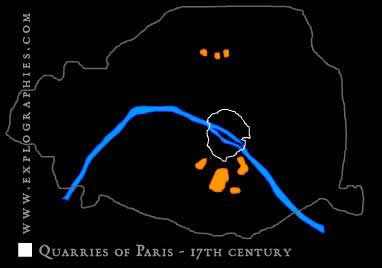

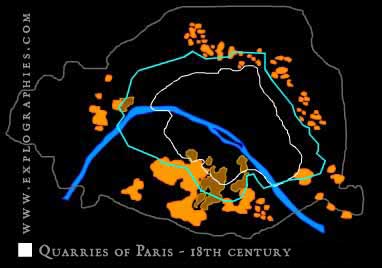

The maps shown are

extremely simplified. Actual limits of Paris are shown in gray, the Seine

river in blue, and in white the limits of paris at that time. Quarries being

exploited (gypsum and limestone) are colored in orange, and the abandonned

quarries are colored in dark orange

|

|

Exploitation from the 1st until 12th century:primitive

exploitation is done in the most instinctive way. Chunks of rocks

lying on the ground are gathered and re-used, and are sometimes

rudimentarily cut. To continue meeting the need in stones, the

compact stone banks flushing with the ground are then exploited,

taking advantage of the stone's natural faults whenever possible

to facilitate its extraction. As soon as the 1st century C.E,

Romans are exploiting the Bièvre valley. Then trenches are dug

deeper and deeper into the stone deposit to extract more stone. A

very old circular open quarry can be found in the heart of Paris,

which was later transformed into an amphitheatre:

Les arènes de Lutèce

(Lutece's arenas).

From antiquity until the middle age, the open quarry exploitation

method requires simple resources but a lot of manpower to be

undertaken. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Limestone is easy to extract

and offers a fine grain stone very well adapted to

constructions; but the extraction trenches prove to be very

costly, their exploitation surface becomes quickly pervasive

yet does not make it possible to exploit the deposit in its

entirety. This deposit is made of stone

"beds"

of different quality,

stacked one on top of the other. They will be exploited in an

anarchical way, with no distinction made between the different

stone layers until the

12nd century.

These stones are used to build monuments, which will later

suffer from the lack of knowledge of their builders, being

degraded by air and bad weather. Gallo-roman constructions will

be taken appart, their best blocks are reused, and extraction

will continue non-stop, progressively heeding the various

qualities found in the different limestone layers to select

those that will offer the best resistances in order to provide

for the needs of this important city that will soon become a

capital city. |

| |

|

|

|

|

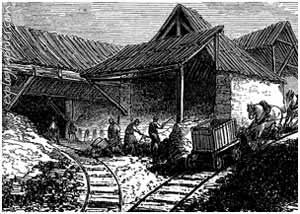

During the 15th century,

this underground exploitation method will spread through the

Paris suburbs in the surrounding plains of Montsouris and

Montrouge. Small new quarries flourish on the surface and

underground. New techniques allow to extract stones of better

quality, in greater quantities. By spreading far from the

quarries entrances, these underground networks will need to be

fitted up with vertical wells equiped with lifting wheels to

avoid an arduous transportation to the surface. These

quarry winches

(or squirrel wheel crane) are moved by a worker climbing the

ladder rungs and allow to lift blocks every time bigger

extracted from the deposit. Sometimes draught animals are used

to activate them. In some quarries, galleries are over-dug and

enlarged to allow chariots, hauled by oxes or horses, to go

around in those networks more and more sophisticated. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Limestone exploitation during

the 16th and 17th centuries :

the development of towns, then

of cities, will progressively increase the population and the

number of monuments. Buildings will need more and more stones,

those from Paris and its region unable to provide the huge needs

of the region, be it in terms of quality or of quantity. The

stonemasons confraternities now tidily distinguish every deposit

and every stone quality to extract the best stones: the "Liais

franc", a very hard

limestone with a regular grain that will make them rich until the

19th century. The stone trade is at the time flourishing, and will

soon spread over our borders. Valuable freight pass through all

Europe to dispatch the "Liais" but also to bring back other stone

qualities sought after in France, in particular coming from Italy,

known for its famed marbles and dark, veined and colorful

limestone: the Carrara

marble. |

| |

|

|

|

|

These huge deposits are

still far from being fully exploited: the price of a

Carreau

(stone tile cut lengthwise) or of

a

Parpaing (stone parpen, cut widthwise)

reaches peaks. The untouched stone

pillars created with the "room

and pillar"

mining method are a financial loss in the deposit, that must be

exploited to the maximum.

During the 18th century,

an italian technique will again improve the exploitation

output. Until then, only half of the deposit could be used. By

"importing" the exploitation method using

"hagues et bourrage",

the output will exceed 90%: all the empty spaces will be filled

(the bourrage) with earth or low-cost extraction wastes that

will be held by walls of interlocked stones:

the Hagues.

At regular intervals, many pillars are placed, directly sitting

on the rock and composed of cubic stones piled one on top of

another to reach the quarry ceiling, creating a very solid

structure. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Today note can still be

taken that, comparingly, consolidation by the

"hague et bourrage"

technique is not subject to pressures susceptible of burst the

rock of a plain-stone pillar or a modern pillar. Being quit of

the stone's characteristic rigidity, it imparts a relative

flexibility that allows it to pack down and to distort, holding

the quarry ceiling on a great surface.

In case of

collapsing, it continues to hold the rock masses without weakening

the surrounding parts via the domino effect. These techniques will

be used by the Inspection Générale des Carrières

from the 18th until the 20th

century, and are

still acknowledged as durable and efficient consolidation works,

less prone to suffer from the effect of time than hardened

consolidations, or stone or concrete pillars. Their reach is

lesser though; both systems complete each other very well for

consolidation work. |

:: Exploitation

and consolidation under Paris

::

Quarrymen of Paris

|

The empty spaces are

exclusively destined to the intensive production of limestone

blocks. Contractors will pay little attention to the future of

their deposit, for which they pay a temporary concession that

must be made the more profitable possible. Quarrymen are well

paid, in comparison of farmers or regular workers. This job,

although hard, allows to live throughout all year, with no

interruptions due to seasons, bad weather or rain. This

explains the great inflow of workforce. The quarry worker is

paid with piece wages, which means he cuts blocks and take them

back to the surface to be paid by the contractor who will take

care of transporting and selling them. More than often a

parallel market starts, outside of concessions. Workers,

sometimes associated to make their task easier, work for

themselves and sell a few extra blocks; the various consessions

cohabit together, sometimes confront eachother or become united.

This underground world is ruled by rules of its own of sharing,

setting of scores and corruption, sometimes participating in

local trafficking or smuggling under Paris.

|

| |

|

|

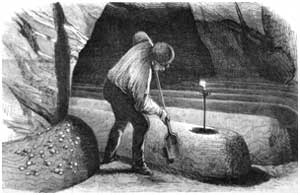

To perform this work,

contractors hire stout men, often farmers coming from the north,

men from Normandy or Britain, who find in this work a

complementary - sometimes principal - income, in exchange of

tiring and extremely dangerous work. Traditionnally, quarrymen

are hired at dusk and are paid at the end of the day. Each

block will receive the mark of the worker - or workers - who

will have taken it out of the stone bed and cut it grossly.

This block will be transported to the quarry entry or to the

nearest hauling well. Work is done in a crepuscular darkness,

dimly lit by oil lamps fed by various sorts of greasy

substances. Contractors sometimes provide fuel, carefully

deducing it from the workers' salaries. These lights barely

provide the light of a candle, but last longer and cost less

than wax. There are nonetheless prone to create accidents,

provoking by lack of lighting various tragedies, notably during

during the extraction and transport of those blocks weighting

several tons across the quarry. Illustration opposite: calculations of masonry left by the workmen of the igc

|

| |

|

|

There

are many victims among quarrymen; falls into badly fitted wells,

only equiped with wooden ladders, and score settings between

workers are part of the risks in this work. Of all the dangers,

the most insidious one is without a doubt the "quarryman

blindness", also

affecting mine workers, which is caused by the poor lightning

these workers are using. Year after year, work in the darkness

irredeemably damages the sight, leaving those with a life

expectancy greater than 30 years completely blind.

The beliefs and superstitions

of the quarrymen are numerous. To insure their protection, they

entrust their fate to saint protectors, of which traces still can

be found. A few chapels, formerly containing statues of "Notre

Dame de Dessoubs Terre" (Our Lady from Under Ground), of Saint

Vincent de Paul or Saint Clément (also

symbolized by a ship anchor) still subsist,

particularly on the Rue Saint Jacques axis. They consist of

round-shouldered, polychrome niches, often painted like churches

with vivid blue and sanguine colors. These beliefs help these

workers in their harduous tasks, as much as wine and liquor, used

as stimulants and anesthetics for the labour of hercules they have

to accomplish: sawing, rock cutting, hauling and transporting

blocks sometimes reaching 10 or 20 tons. |

| |

|

|

The work rythm goes at high

pace, the worker (see hierarchy hereunder)

works seven days a week, but can rest one day every five weeks,

the day following the payment of the monthly salary

(this day is always a sunday).

These conditions don't seem to be excessive for the time and

the workers make do with their "inducements" granted by their

employers, who rarely have troubles with their employees, even

if those are reknowned for their fierce temper. The best

workers and foremans are sometimes allowed to cultivate the

lands above the exploitation... if they find the time. out of

work hours, the quarry worker is often too tired to do any

domestic task, and it's his wife who takes care of the

household. The employer can increase his income by providing

housing barracks for his employees and deducing, in addition to

the general expenses, the lodging he gives to his employees,

who in turn become completely dependant on him. In return, the

employer guarantees them work, housing and a yearly income

which will allow the luckiest among them to feed their children

until they are able to take their place. |

:: Hierarchy of

quarry workers ::

-

workshop men

-

:: Les

hommes d'atelier ::

they transport the blocks

from the extraction spot to the extraction wells, and participate in the

bank-up and gross consolidation works.

-

-

Piece-workers

-

:: Les tacherons ::

they execute the worst

tasks, are slightly better paid but are only employed during periods of

high activity in the quarry

-

-

Foremen

-

:: Les conducteurs

::

They lead the teams, hire

new workers and keep track of the stones count for each worker. They are

of course the best paid.

-

-

Quarrymen

-

:: Les carriers::

They are specialized

workers who extract the stones and get paid for each stone delivered to

the contractor.

The 'quarryman' term is

generally employed for all of those who work in a quarry (underground or

open)

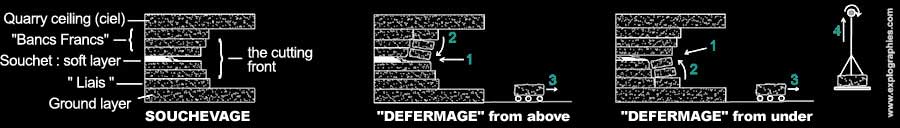

Souchevage and Defermage

techniques

|

The

stone bank exploitation technique during the golden age of the

"master quarrymen"

from the 16th until 19th century roughly stayed the same. First,

low galleries are dug, from which the first blocks are

extracted. In the quarry, well defined work areas are fitted

up: the area where the stone will be exploited

(the workshop)

and the area where it is extracted and that will first be

consolidated

with pillars then with the "hagues

et bourrage"

technique described in the precedent chapter.

Souchevage technique

in an

underground quarry

The Souchevage technique-

Illustrations © explographies.com

The workshop presents the cutting front

(Front de taille),

which is the massive limestone deposit where the blocs are

extracted from. Blocks are separated by natural separations

(geological layers)

where each stone quality appears separated by lines, presenting

various matters of various density. One of these layers, very

soft, is called a “

Souchet

”

gives its name to the “Souchevage”

technique which consists in digging horizontally between these

layers

(1).

If this term sounds pretty abstract, one can

compare it to a big wooden plank that one will cut following the

horizontal lines of the wood, then cut it vertically to make

smaller plancks.

|

Abattage techniques in an

underground quarry

The Abattage technique-

Illustrations © explographies.com

|

After the Souchevage, the

limestone slab is cut from above and from under. To detach the

block of rock, it will then only be necessary to cut the sides of

the slab, preferably following the natural faults and fractures of

the stone to make the process easier. This is what is called the

rock “Defermage”

(2),

which will be done using a “busting

wedge” inserted into

the faults, metallic lances (similar to crowbars) and various

tools like the “Esse”,

a hammer used to cleave or dig the rock.

The

souchevéed

then déferméed

block will detach itself from the cutting front under its own

weight. It will then be grossly cut then transported on wood logs

(3)

and hauled by

chariots to the quarry entrance or extraction well (4)

where it will

be dried and cut into rubble stones by the stonemasons. This is

how the underground quarry exploitation takes place: galleries

will be dug progressively, rock will be extracted and the empty

spaces left will be consolidated to go further into the

underground depths. |

Quarrymen

© explographies.com

|

These extraction methods will

be used in Paris and the entire Parisian region. In 1810, a decree

will definitely prohibit the underground quarries exploitation in

Paris, then progressively in the entire Parisian region. This date

will coincide with an extraordinary invention: concrete. This

invention will soon allow new architectural audacities and will

give the possibility to build higher, faster and moreover, will

let builders to

precisely know the charges and resistances of building materials

who will stay the same, bringing new perspectives to the stone

builders in the 19th and 20th

century. Transition will be immediate. In a few years, concrete

will supersede rock. The transition will sometimes be so brutal

that some quarries will be abandoned leaving tools, lamps and even

the last extracted blocks on the spot. Very few quarries will

continue to be operated into the 20th

century, in a world where progress is synonym with concrete and

steel.

The last suburb quarries

will fade out progressively sometimes recycled in mushroom farms

where the white Paris mushroom will be cultivated on the old

quarries exploitation embankments. A few former quarrymen will

thus find a way to change their profession in these mushroom

farms. In 1939,

Bagneux closed the

very last underground quarry still exploited in the Ile-de-France

region. |

Gypsum

exploitations

|

|

Gypsum and limestone under Paris

: The

underground quarries of Paris have mostly been exploited for

their limestone deposits. They represent 770ha of the city’s

area, to which 150ha of gypsum quarries can be added. The

layout of these exploitations is clearly delimited in the north

tier of Paris, leaving the limestone area to the south. This

gypsum (called ludian gypsum) is a geological formation, with a

completely different composition from the limestone (called

lutetian limestone, after its era of formation)

To explain is particular

localization in the north of Paris, one must go back to the

circumstances of its formation: Without going into technical

details, one can say that a long time ago (approx.

50 million years ago) just before the start of

limestone formation, a “small”

crust fold raised all the south part of the Parisian basin. The

sea then covered several times this region, leaving a lot of

particles that agglomerated themselves during 15 million years

to create the whole limestone bank.

How is gypsum formed

?

Immediately after that time,

the sea retreated and left behind basins (small lagunas) in which

fragile gypsum particles formed, crystallized and accumulated

themselves during approximately 10 million years. The successive

deposits from this sea coming from the north were then stopped by

this geological fold (the Ypresian fold), forming a sort of dam on

the upper plateau south of Paris. This is how we obtained subsoil

composed of very shallow, high gypsum concentration to the north.

To the south, with no covering layers, it’s limestone that can be

found almost at ground level. This shallow depth (between 20 and

30m) made it easier to exploit those rocks.

Gypsum’s particularities

: Compared to

the limestone, gypsum has the particularity to “dissolve” when in

contact with water. One will then ask how such heights of rocks

are still present yet and weren’t just simply eroded a few years

after being formed. That was the case in a few places: water

(sea

water, rain infiltration) made everything disappear. What is left

of those gypsum deposits only exists because of a thick layer of

clay formed on top of it right after, which protected these

soluble crystals from infiltrations. This small geological chapter

will allow us to better understand immediate applications of

gypsum: it dissolves when in contact with water, but also makes an

excellent “cement”. This is how some gypsum deposits will

naturally become plaster exploitations. |

|

|

Gypsum exploitation mainly

consisted in using the crystals to transform them to obtain a

powder which would then serve as mortar. The upper part of the

4 gypsum deposits on the map will be used. On the side drawing

is shown the Butte Montmartre and the Sacré Coeur church. Right

under, in the subsoil, are the church’s foundations, stretching

out deeply into the soil, at almost 40m under the monument’s

level, sustained by anchored pillars put into the gypsum

deposit, that will of course not be exploited under the church.

Those big gypsum deposits will be dug in the same way limestone

is, to extract the material. This exploitation will simply be

done with greater depths, given the size of the available

deposits. Each layer of these 4 deposits representing an height

of 50m will receive a colourful name, given by the quarrymen to

differenciate them:

les fleurs

(the flowers),

le gros cul

(the big ass),

les foies de cochon

(pig livers), les

pots à beurre

(butter pot) ou

les crottes d’anes

(donkey droppings)…

|

| |

|

|

|

|

This very old plaster use

dates back to the romans, who used the flushing deposits to

make certain mortars. In the 18th and 19th century it will

undergo an industrialization process that will transform the

Montmartre, and buttes-Chaumonts quarries, and soon those in

the north of Paris (Cormeilles, Triel, Livry,

Gagny…) in gigantic plaster processing plants that

will provide 2/3 of the national production, leading to mortar

exportations for the United States (giving

their new name to the Montmartre quarries, the “America

quarries” – les carrières d’Amérique). The deposit

will be exploited using explosives; the upper and lower stone

banks will then be extracted using manual tools, creating very

regular architectures with high, round-shouldered, almost

triangular shapes typical from gypsum quarries. The top of the

superior gypsum mass will be consolidated with wood timbers,

forced inbetween the different cutting fronts, forming some

sort of woodwork made with joggled beams.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

The mineral will then have

to be taken out of the quarry, using ox or horses teams, or

pushed on wagons on rails. In the nearby plaster processing

plants, blocs are crushed, grounded then heated at 150°C in

furnaces to obtain a whitish powder that will be used pure or

sometimes slightly mixed with starsh, or with some retardants

for slow drying mortars. Those quarries thus present only one

problem, precisely this capability to dissolve into the water

used to produce the mortars. Only a small crack or a small

water infiltration in the clay layer forming a protective

blanket over the gypsum would be enough to transform all the

empty spaces left by the quarrymen into a card castle. |

This mechanically weak rock opposes no

resistance to ceiling cave in, the phenomenon behind many collapses which

occur more easily in the limestone quarries. This is why there are, a

century after, completely unbuildable, desagregated areas which could be at

best blasted to make them disappear, or be blocked up to prevent any

accident.

How does a cave in form itself?

Cave in mechanism

(pop-up window)

Illustrations:

1-

Section

of the ‘America quarries’ (carrières des Amériques) under the Sacré Coeur

church

2-

Quarry ceiling consolidation with

wooden beams

3-

Gypsum furnaces of the gypsum

quarries Montmartre

4-

Majestic gypsum quarry in the Paris

suburbs with wood shorings

The

Mushroom Farms

|

|

The end of the quarries

exploitation :

At the beginning of the 19th

century, the intensive exploitation of the quarries will stop,

provoked by the sudden appearance of concrete and the banning of

stone extraction. These huge underground cavities will be

abandoned from one day to the other by the quarrymen who had been

living from this activity for several generations. This useless

space will not stay unexploited for long, because a Parisian named

Chambry

will discover by luck the fortuitous link between the quarries

existing in his neighbourhood and the spawning of mushrooms on

horse manure…

The discovery of mushroom

culture in Paris :

Going rapidly from

discovery to culture to commercial exploitation, customer demand

will never cease to grow, in such a way that our entrepreneur had

to buy new quarries in Paris (under the Rue de la Santé) to expand

his exploitation, then in the suburbs, so promising as this

activity seemed. He would soon be imitated by other operators who

rapidly figured out they could make their fortune by growing the

Paris mushroom. Those abandoned quarries will soon become as

prized as they were at the time of quarrymen, and will be

transformed into real underground culture fields. In the 40’s, the

production reaches 40 to 50kg of mushrooms produced per year and

per fathom. Given that there are around 20 exploitations around

Paris, and that each exploitation contains around 20000 fathoms,

the total production is around 2000 tons per year which is not

inconsiderable. |

| |

|

|

|

|

The biotope of the Paris

mushroom : Mr Chambry’s

secret

is a completely natural recipe which results from air temperature

and humidity, particularly constants in the quarries. The absence

of light also favourishes this culture, who only works whimsically

with daylight. The environment being

almost ideal, it’s only a matter to add the elements needed for

the mushroom culture: it grows only on horse manure with a special

quality and origin, after having undergone

a particular fermentation.

Manure fermentation

:

To begin with, haystacks

(called parquets)

measuring 1,20m are made with manure near the mushroom farm. This

manure will ferment and release a certain heat. According to

mushroom growers, if the haystacks are shorter, the manure won’t

produce enough heat. If they are bigger, they will produce too

much heat. After three weeks of this

alchemy, they hay obtained in the “parquets”

will have undergone a chemical fermentation that will form the

right component for mushroom culture. The parquets will then be

transported into the mushroom farm through the former extraction

wells equipped with simple ladders, or directly through the main

quarry entrance.

Culture and alchemy of

mushrooms :

Once it is in the quarry, the

manure will be spread evenly in a cord shape , measuring 40cm of

height by 40cm of width. This operation is called “montage”. These

dimensions were set with time and experience by the mushroom

farmers. This will let the manure ferment once again, to reach a

temperature of 18 to 20°C. The second step is called the “lardage”

(larding), consisting in sowing the haystacks by punching holes in

them and introducing small wafers of dried manure (called “mises”)

containing the with part of mushrooms, appearing in the shape of

white filaments radiating through the “mises”

The seeds will constitute the

most important investment for the mushroom grower, since he’s not

cultivating them himself. The haystacks are then smoothed to

become very regular in shape, and after waiting 20 days for the

germs to take hold in the manure comes the next step: the “goptage”.

It “only” consists to cover the haystacks with a 2cm layer of

sand, using a wooden plate (“taloche”). This step will give the

haystacks their white, smooth aspect. Later on, this sandy layer

will be obtained by grinding the quarry stones in a very fine

powder called Craon

by the quarrymen. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Picking and maintenance of the

mushroom farm :

4 to 8 weeks after the

goptage,

the mushrooms are ripe for picking. Cultures must be maintained in

a humid atmosphere during the picking period by being watered

regularly. To “breathe”

(pick up oxygen and

release carbon dioxide),

mushrooms will need a constant airflow and a temperature of above

14 °C.

Mushroom farmers are thus very watchful about air and ground

temperature to maintain their cultures in an ideal atmosphere. To

keep this warm and humid environment, some mushroom farmers

install boilers atop the ventilation wells, in which they will

keep a continuous fire that will help circulating the air in the

quarry while keeping it warm.

Some others will move their

cultures, depending on the season: close to the entrance during

summer to let the warm air enter, and far into the quarry during

winter to maintain it inside. At the end of every picking, called

“volée”,

the same operation will be renewed by sowing the haystacks anew.

They can be reused for up to 5 “volées”

before the manure becomes depleted of its nutrients and becomes

unusable for culture. The manure is then gathered in a special

cellar, and sold for market gardening. Its selling price allows to

fully compensate its buying price.

After that, the quarry must be

cleaned completely

before the whole process can be started again. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Set up of a quarry as a

mushroom farm :

Most of the area is dedicated

to mushroom culture. Some rooms or cellars are kept to store away

tools, replenish the stocks after the picking or keep the old

manure until it is sold. At the entrance, like in any

exploitation, an office along with a deliveries and weighting room

can be found, and for the most important mushroom farms, even a

lampisterie, which is a room to store carbide lamps. The quarry

must be perfectly clean to avoid diseases which could propagate

and contaminate all the haystacks at once. The walls are

whitewashed from the ground and up to a height of 3 meters, by

applying quicklime on them; this is the reason why many quarries

have white walls, following upon the whitewashing.

Other foes are watched closely

by the mushroom farmers: rats, mice and fieldmice destroying the

cultures must be kept under constant surveillance. Insects too are

attracted by the “whites”,

like ladybugs, and flies who are avid consumers of young

mushrooms. They are kept at bay by

naphthalene powder, periodically

spread around in the quarry; it is used with extreme care as not

to affect the cultures. Last but not least, another unexpected “predator”

is under a permanent ban to visit some mushroom farms:

women

:-). Be it an old belief or a well-founded experience

(for which we will not look for an explanation), many mushroom

farmers fear them: according to books from this time, they are an

“irredeemable source

of damages while being present, even temporarily, during certain

periods of the month”. |

| |

|

|

> > |

|

Quarrymen and mushroom farms

: We can

conclude this small chapter on mushroom farms by emphasizing

the fact that some mushroom farmers were quarrymen before

starting this activity. Their experience in this field will be

very useful to fully exploit the natural “resources” of the

former gypsum and limestone quarries. By using rock powder (craon)

or the embankment materials used to consolidate the quarries

for the haystacks

goptage, They

will literally empty the consolidations done over the past

decades to strengthen the galleries. Remnants of those

consolidations can be often found by simply observing the

presence of “pillar

forests”,

formerly sourrounded by Hagues containing the embankment

materials, now completely isolated. This space emptying also

has the advantage to free the ground area in order to extend

the exploitation as much as possible.

This is also certainly thanks

to their experience from working in the quarries that the former

quarrymen will conserve the most important consolidations, keeping

a certain logic in their disassembling, without putting the

mushroom farm in danger. |

Quarries' General Inspection

The history of IGC starts in the middle

of the intensive exploitation of the quarries in Paris and its region. The

capital city’s subsoil and that of its suburbs has been extensively

excavated, leaving behind huge abandoned and barely indexed voids. On

hundreds of acres, almost without durable consolidations, lie the buildings,

ever taller and more numerous, of a huge city: Paris.

Inevitably, huge collapsings will happen in the capital city. Land, houses, and

even entire streets will sink in the ground. In 1774, the disaster that will see

the Rue d’Enfer swallowed by Earth will terrorize the Parisians: the

street is now called Boulevard Saint Michel, in the very center of Paris!

After

this tragedy, the royal power will be forced to react on this matter of first

importance. The first studies end up being catastrophic: the underground

quarries are huge, completely unstable and nothing has been planned to contain

this imminent danger. A specialized service will be urgently created in 1776 to

try and face the problem…

Collapsing

in the capital city

|

|

The first months of

this new service unfold amid a certain puzzlement. A new sequence

of collapsings in 1776 adds up to the unease and the panic

feelings of the Parisians who fear an unavoidable sequel of global

collapsings, or the sinking of the whole city underground. True, a

peak regarding danger has been reached, but this sequence of

accidents is only a statistic. The “conseillers

du Roy” (the

king’s advisers) are nonetheless in uproar, and two

distinct services will be created at the same time to try and

solve the same issues, with a sure rivality contention feeling.

The fight for power will soon turn into personal score settings,

and will end with a decision disavowing the commission appointed

by the finances service and led by M.

Dupont, to the benefit of

the Inspection des Carrières

led by Mr. Charles Axel Guillaumot. |

| |

|

|

|

|

The

quarries service must bring a quick and thorough answer to the

problem. The immediate imperative will quickly determine the

main lines of Guillaumot’s field of action and that of his

successors. Generalized collapsing has seen public roads,

buildings, men and horses swallowed into a chasm previously

unsuspected by the Parisians. For the gullible citizen living

in this part of the city, more than even the catastrophe

itself, the damages or the victims, it is the unspeakable

terror of superstitions and old

beliefs that resurfaces through this geological demonstration,

easily blamed on the diabolical spirits living in the entrails

of Earth; popular fears to which the king vows to bring order

to. The quarries service will then receive four missions:

inspect

the underground voids, repair

and consolidate them, proceed to

the mapping of the ground and

inform about the outcome of their studying. |

Missions of the "Inspection des

Carrières"

|

|

The

quarries’ inspection will

begin by the damages done on the surface, more as a move to

show presence on the ground and appease the Parisians than to

fill the voids created under the streets. This inspection

mission will become paramount for the IdC that will need to

know before all things the extent of the quarries, explore them

and identify the various mechanisms and dangers that could

affect the cities that jut out over them. This exploration will

first start with small teams of sub-inspectors, engineers and

surveyors under Guillaumot’s orders.

Geology

in the 17th century is barely beginning and Guillaumot must, in

order to spot danger, identify its causes and the mechanisms of

an unknown world. Geological layers formation and the age of

Earth will appear only a century later: this speaks about the

difficulty of Guillemot’s work and that of his teams. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Consolidation and repair work :

Before the enormity of the catastrophe,

adapted works to fill up the crevices and build the streets again

must be realized. Guillaumot will have to work under urgency in

order to rapidly conceive an action plan to circumscribe the

collapsing effects. The former finances commission, still very

influential, watches closely all the undergoing operations,

infuriated from having been put aside to the favour of the IdC.

New

techniques will have to be worked out to consolidate the cave ins,

through masonry and landfill, the comforting of former galleries,

entrances, inspection stairs, teamwork organization and the choice

of the most adapted materials. This titanic operation will have to

be partly delegated to private contractors, paid for each task, to

accomplish each work part done by dozens of specialized workers,

paid by the subsidies granted by the king, then by the city of

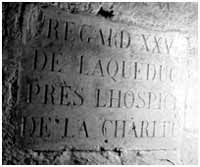

Paris, to the quarries service. Every work will be traced by a

specific historized classification, which will allow the

identification on carved stone slabs of the work nature, the

realization date and the supervising inspector’s name. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Underground mapping :

This mission, following the first two, will

inevitably have to be done do give the service a reliable tool,

showing in the most precisely possible manner all the inspected

voids, all the works done and all the identified dangers or those

that were circumscribed by consolidations. Entrances, drilling,

wells, everything must accomplished by a few men who will write

down, gather and reproduce all their handwritten notes to create

the first underground maps of the city and its surroundings.

The most

dangerous voids will be immediately filled, blocked or even

collapsed with explosives after having been mapped as precisely as

possible. All of Guillaumot’s engineers and surveyors team will

accomplish this remarkable work in a record time. The maps will be

modified, made more precise by their successors, to become 1/500th

then 1/1000th scaled maps. They will give in 1855 the first “Paris

city underground quarries atlas”, still used today in its modern

form (the IGC maps). |

| |

|

|

|

|

The

information mission entrusted by

the king to report the actions taken and the service’s results to

him, will later on be given to the administrations. It will stay a

secondary mission as long as the inspections and above all the

most urgent works will stay incomplete in the quarries voids.

After a century and a half, they will eventually be over. The IdC

will soon become the “memory” of all the underpasses, equipped

with archives showing the nature and the localization of the works

done in the former underground exploitations.

This is

today one of the most important mission of the modern IGC, which

settled its activity on informing the general public,

professionals and the administration about the dangers linked to

the underground world. The general public will then be able to

know before buying a house if it is built on “undermined”

land. The research departments, architects or public work

companies have the obligation to do so; Informations are given

based on precise maps of the underpasses, and on the disaster

prevention plans realized globally, particularly for the cities

surrounding paris as well as in the immediate suburbs.

|

The origin of the Paris’ catacombs name

: They were in a certain

way baptized by their spiritual father, Louis Hericart de Thury, who hesitated

for a long time to give them an exact name. They make reference to the catacombs

of Rome, Greece and Egypt, against which the engineer wants his project to

compete in terms of magnitude, even hoping that they will surpass the catacombs

of old. He will devote many pages in his book “Description of Paris Catacombs”

on this subject, looking for a correct ethymology and an equivocal meaning. The

words “catatombs”

(catatumbae) and “catacombs”

(catacumbae) have meanings relatively close, translated

according to the ancient etymologists as underground places, as well as burials

grounds where the first Christians and first inhabitants of Rome celebrated

their deads. He will conclude this linguistical research by this brilliant

expression: “I found this

denomination (catacombs)

so well established that I didn’t find the need to change it”, precising

however that the most exact denomination is “general ossuary of Paris”.

Consolidations

techniques

|

|

The

first “natural”

consolidations where realized by letting in place masses of

limestone, to sustain the empty spaces remaining after the

stone extraction. These pillars, usually of great size,

continue to play they part and provide a good support of the

subterranean cavities, as long as they are present in

sufficient numbers. Some religious communities, mindful about

the durability of their legacy, also realized works under their

buildings’ foundations. The

Carthusian order possessing 3

quarries under Paris realized a few arrangements of this sort,

even if there aren’t many traces of it left. In the same

manner, the 18th century consolidations done under the Val

de Grâce church by François

Mansart and those of the Paris

observatory supervised by Perrault, consolidate even more the

buildings standing on top of them. There’s no doubt those

gigantic piece of works exceed the real needs, but continue to

subsist through the centuries in a very remarkable way. They

are big-sized brick work with low archs and massive pillars,

craftily placed to sustain the whole quarry ceiling,

forestalling that way the different geological accidents that

could interfere with the masses’ equilibrium. At that time, the

works will be regarded with less enthusiasm, given the enormous

amount of money needed for their realization, especially those

of Mansart who will lose his title of royal architect for

having exceeded the credits granted for the entire construction

of the church just with the underground works. |

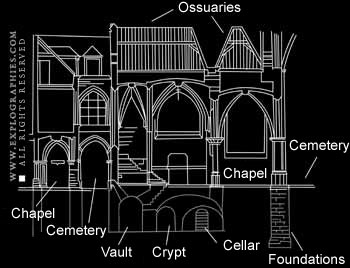

Exploitation and

consolidation methods in the old Paris quarries

Exploitation and consolidation

methods in the old Paris quarries

A -

Mass, ‘turned pillar’ or

preserved cutting fronts (on the left), and void consolidated by pillars and

hagues maintaining the filling material

B and C –

Galleries bored directly into

the limestone mass

D -

Gallery bored into the mass,

and void (on the right) consolidated with supporting walls intersected with

filling material

E and F:

Galleries consolidated by

walls made by the IGC and gallery with corbels (floors are on the upper part)

|

|

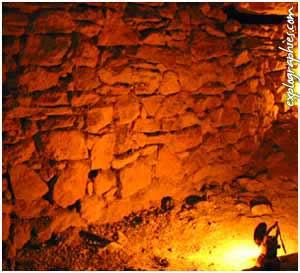

1-

worrying about details :

The works of the IdC are inspired after

older consolidations and the architectural progresses of this

period. A remarkable attention for detail and for perfectly

realized work will orchestrate in these underpasses a debauchery

of financial means, of craftsmanship and engineering. These

achievements surpass by far the aesthetical requirements of our

time, if we consider them according to our actual appreciation

criterias. The quality of stone work, the equipment of masonry and

the audacity of the work can be compared on all aspects with the

quality of surface work for the building of prestigious monuments.

This astounding finishing quality are justified by the perfection

mindset found in realisations from the 19th century, guaranteeing

the strength and durability of the work.

2-

worrying about effectiveness :

The

most common void consolidation process includes the use of dirt,

sand and rock extraction wastes coming from the quarries

themselves. These considerable amounts of material often are

brought from the surface, to fill the “unnecessary” voids (those

with no practical use by the inspection), the “uncertain” voids

(those that could evolve into a collapsing or with

faults presenting safety risks) and the “searching”

voids (galleries dug into the mass in places

where subsoil composition is not known). These

embankments constitute the main part of the former voids, filled

with mechanically weak materials, but spread on important areas as

to limit the impact of a possible subsidence while still

continuing to support the quarry ceiling in an even manner.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Those

embankments will be associated to other works made to reinforce

them. For example, partitioning walls will be used, placed every 5

or 6 meters in filled galleries to reinforce their structure

(symbolized on the maps by thin red lines forming

hackings with beige background). In more important

spaces, a “cobweb” architecture is used with small interlocked

walls, interspersed with small spaces filled with material. This

technique, which can be qualified as “reinforced

landfill”, is quite similar to the

“hagues et bourrage” technique used by the quarrymen then by the

IdC, consisting in surrounding or containing these embankment

masses with strongly interlocked dry stone walls. The “Hague” term

supposedly has a Germanic etymology (from

khag=enclosure, later used in the Saxon and Viking languages,

before being frenchified) and designate several types

of constructions, sometimes formed with regular lines, like a

classical wall, or an entanglement of rocks assembled according to

their shape in order to give them more stiffness.

(hagus insertus) |

| |

|

|

|

|

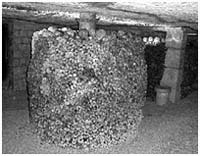

These

hagues are regularly interrupted with pillars, formed by blocks of

massive stone measuring 60cm to 1m in

width, piled one on top of the others

then adjusted between the quarry ground and the quarry ceiling.

Those pillars aren’t made through masonry and hold in place under

their own weight, hence constituting a simple yet very effective

work. Sometimes this kind of consolidation is used in a specific

place to sustain the quarry ceiling tending to subside or crack.

Some of

these pillars reach considerable heights, sometimes 10m and more

implying the need, given the size of the blocks used, for

scaffolding, pulleys and important lifting means to place the

blocks weighting several tons so high. Other pillars, more modest,

are simply used to sustain “low” galleries exerting a high

pressure, and are constituted by smaller blocks but of equal

resistance. |

| |

|

|

|

|

These basic constructions,

commonly used by the quarrymen and the IdC workers, will be

enriched by a multitude of built structures made of cut rubble

stones assembled by

different varieties of mortars and limes

(Tournay lime, Senlis lime…)

which harden with humidity. Those absorbent mortars hold extremely

well in the humidity-saturated air and allow building walls that

will sustain in priority the inspection galleries located under

the streets, creating some kinds of doubles for ancient galleries,

right under the front face of the buildings, to guarantee a better

stability for the surface constructions. The major part will be in

a perfect straight line, sometimes forming a diagonal rib on top

or ending up in a corbel, distributing the load on several

intercalated floors. In some other parts, liais slabs will be

juxtaposed to form a double ceiling, maintaining and protecting

the gallery from the quarry ceiling. This same method is used to

build massive pillars of 1m50 of cross-section, adjoining

galleries and interrupted with regular hagues holding embankments.

Some of the walls end up in staggered rows, with no straight

border, as if they were unfinished. They are in fact “opening

walls” (murs

d’ouverture) or “waiting

stones” (pierres

d’attente), left open-sided to allow the continuation of the

work later on. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Ultimately, some truly

exceptional works can be found, worthy of belonging to the most

beautiful subterranean architectures of this time. Monumental

stairs joining one or two different gallery levels, with

perfectly set stones, straight or spiral staircase, sequences

of arches of gothic inspiration and of course, collapsing

consolidations in shapes of domes or massive arches, sometimes

reaching up to 10m above the ground. Some of the cave ins are

consolidated from the top and need some drilling to reach the

summit. Mortar and aggregate material is then poured into it,

filling all the spaces compartimentalized by masonry work to

keep them in place. These works, sometimes invisible, are all

indexed by carved stone slabs précising in this case

F.R

(Fontis remblayé, filled cave in) followed by an

upward arrow

(filled from the top down) or a

downward arrow

(filled from the bottom

up). |

The

modern quarries inspection

|

|

The

methods will of course evolve and continue to be used by the

modern IGC, whose mission will more or less stay the same. At

the end of 19th century and beginning of the 20th century, the

collapse with explosives will be largely used. This method,

notably used for the gypsum quarries for which the extent and

dangerousity is measured, will reveal itself less drastic that

what was previously thought. The method, often uncontrollable,

leaves behind unreachable but potentially dangerous cavities.

The

limits are quickly reached for this system completely at the

opposite of the lasting work previously done, that moreover

could be inspected regularly based on the maps annoted to keep

a trace of each detail. After the explosive collapse the old

location of the quarry remains, indeed filled but whose

evolution will be unknown and will afterward prohibit any

construction on the corresponding area.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Concrete

and modern techniques will then be used more regularly

afterwards. The IGC standardizes 1,40m cross-section pillars,

reaching variable heights, depending of the size of the

fractured area presenting a danger of collapsing. They are in

fact very similar to the pillars built by Mansart, which proved

their solidity for more than 3 centuries. The top of these

massive pillars holds the quarry ceiling and stretches on the

side to reach the top of the next pillar, where pressure forces

meet. The filling method by injection will then be used where,

after a well-sized drilling, large-grade dry materials are

poured into the cavity. Liquid injections are also used,

needing smaller drilling. They can consist of mortars or

oil-bearing wastes to fill and impregnate the embankments,

hardening material (bentonite) to form a compact mass, or with

liquid sands (low cost).

|

| |

|

|

|

|

In

certain cases, consolidation can be done using concrete

pillars, injected in circular cofferings set in important

numbers, or through drilling and micro-poles between 110mm and

115mm in diameter closely spaced, that will be fitted in

through the drilling. A variation of this method consists in

bolting the quarry ceiling by inserting metallic rods,

sometimes assorted with a ceiling-sealed lattice, sometimes

covered with concrete flocking… these methods are very costly

and their long-time durability hasn’t proved itself outside

from research departments, projections or theoretical

calculations. Note can also be taken that in some places, part

of the underground legacy is preserved and that “old fashion”

consolidations (rock pillars) are spoken of again.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

This

tour of underground consolidations would be incomplete without

mentioning a specific type of work set in place at the

beginning of the quarries inspections and maintained

pre-emptively : ventilation shafts,

which have almost completely disappeared in Paris. A good part

of all these costly operations would have probably been useless

by respecting a few simple methods, consisting in keeping good ventilation in the quarries and inspect it regularly to

observe its natural evolution. These numerous shafts were meant

to let a current of air flow through the galleries to dry the

stone and thus prevent the progressive damaging of the

limestone masses, weakened by the accumulation of humidity.

illustrations:

injection in the Rue Claude Bernard in 2002. (1) Drilling

and injection pipes installation (2) Connection with the

compressor (3) Drilling seen from underneath just before injection

! (4) Concrete-mixer and injection of the gallery. |

Photos & Illustrations © explographies.com

-

Credits : Dragon & nexus - All rights

reserved -

Inspectors and inspectorate since 1777

The setting in place of the quarries

service

|

|

This story, started the 4th of april 1777,

will know a succession of inspectors more or less renowned, that

will continue during their inspectorate the immense task started

by their predecessors. Detailed biographies of each general

inspectors from 18th and 19th century are available in the Ecole

des mines annals. Here we will only keep the principal facts that

happened during their inspectorate, linking them to the

explanatory carved slabs affixed to their work. After the

beginning of the 20th century, dates will not be specified on

these slabs any more; most of the consolidation work had already

been done during the previous century. The quarries inspection

mission will then evolve considerably toward a technical and

consultative role, based on the maps updating work, often updated

and sometimes made by surveyors for the uncharted sectors. |

| |

|

|

|

|

We will

remember from this brief sum up of the IGC history the setting in

place of tools and of the principal organization defined in 1777

by Guillaumot, reaffirmed and optimized under the work of M.

Hericart de Thury. The principal inspection mission of the IGC

will initially be done with reduced teams of technicians, all

lacking experience in this field since nothing comparable existed

before. This is therefore based on everyone’s personal

capabilities that Guillaumot will manage his service appointing

engineers, surveyors and technicians to oversee and do the work.

Firstly, the geological mechanisms will have to be observed, at a

time when serious theories on geological formation are just

beginning to appear. They will need to compose between their sense

of observation and their adaptation capabilities to measure the

dangerosity of a rock formation and the ways of proceeding with

the necessary works. |

| |

|

|

|

|

To

complete this technical aspect of the works, a classification

system will be set in place by Guillaumot in 1778 showing the

year of the works, the inspector’s initials and the

consolidation number. Consolidations from 1777 having been done

already without being classified with ivory black-colored stone

slabs, they will all be classified with a year of delay. An

ingenious network of quarry depth measures, indexed on a

standard based on the level zero of the river Seine, will be

added to the system, allowing to know precisely the galleries’

localisation compared to the ground level and their real

altitude. These methods are still used nowadays on modern maps

which possess altimetric measures and the same space reference

points, more than 250 years later. Finally, and this will

represent a small revolution at that time, measurements done so

far in inches and feet will all be converted to the metric

system. A similar work will be done during the napoleonian

empire, with the re-numbering of buildings in each street that

will be observable underground and on the maps, since they will

be precisely labelled by the quarries inspection.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Guillaumot will test all sorts of consolidation systems,

reusing the quarrymen techniques and trying to find innovative

ways, like these masonry works resting on series of lowered

arches to distribute the weight, that can be found in the south

of the 15th arrondissement quarries network and under the old

railway axis under the rue Saint Gothard. The same experiences

must have been applied to the mapping to come up with an

effective survey system, but there are almost no traces left of

the measurements made at that time by Guillaumot’s teams. The

last phase of the service’s setting up will be the arrangement

of the municipal ossuary; this is the work of two inspectors:

one will have to find the ways to bring and pour millions of

bones in determined sectors, the other the ways to show them

off while respecting the memory of these millions of graveless

remains. |

Photos & Illustrations © explographies.com

- All rights

reserved -

A century and a half of inspectorate

|

The table cites every

inspector from 1777 until 1909, showing in white their name and

their inspectorate period, and in orange the kind of slabs they

used to designate the works they realized, as well as a brief sum

up of their achievements.

Antoine Dupont - 1776

90, 93 ...

This mathematics

professor, appointed by the finances bureau will never be named

“quarries inspector”. He will nonetheless assume the same

functions for a few months and will start the first official works

in the Capuchin quarry. Dupont will be deposed and will spend most

of the rest of his life trying to discredit Guillaumot, appointed

in his stead.

Guillaumot 1777-1791 (first

inspection period)

I.G.1777 or

I.G.XIIIR

He will be the

founding father of the service, to which he will devote 30 years

of his life. Guillaumot will become famous through the

consolidation works of the Rue Saint Jacques, the reconstruction

of the Mansart staircase and the transfer of the bones to the

municipal ossuary.

Duchemin 1791-1792 -

Demoustiers 1792-1793 - Bralle 1793-1795

I.D.1792 - ID2-1793

- I B1794

These three

sub-inspectors will, one after the other, continue Guillaumot's

work and guarantee an interim period of one year each, to enable

the continuity of the works started by their former "boss" who

will definitely stay as their model. They will be accompanied by

the same teams who will do maintenance works for 4 years.

Guillaumot 1777-1791 (second

inspection period)

I.G.1777 ou

I.G.XIIIR

After some serious

politico-judicial adventures, Guillaumot, who had been deposed in

1777, is reinstated at the head of the service. He resumes his

work in the Val de Grâce, the vaugirard quarter, the

Rue Dareau as

well as in various quarries networks near Paris in the 13th, 14th

and 5th arrondissements.

Administrative committee

1807-1808

C Mon 1808

After Guillaumot's

passing, no candidate seemed to be able to show the same

capability to lead this service. The quarries inspection is then

entrusted to a commitee that must take care of the administration

and taking care of current affairs. The works of the committee

will only be occasionnal and always driven by urgent issues.

H.de Thury 1809-1831

I HT 1815

It is a brilliant 30

years old young man, specialized in drilling wells, who will be

appointed to restart the activity of the quarries inspection. The

most prolific of all inspectors will realize countless works,

monuments, wells, and will realize the arrangement of the ossuary.

He will introduce a geological and scientific dimension to the

inspectorate and will write two reference books, before ending

his career at the science academy.

Trémery 1831-1842

1 T 1840

First sub-inspector of

De Thury, he will learn along the same lines. His inspectorate

will last more than 10 years, during which he will particularly

take care of the Montparnasse, Vaugirard and Tombe Issoire sectors. Trémery will leave his names in the annals for the

realization of a square well located in the Capuchins quarry.

Juncker 1842-1851 - Lorieux

1851-1856 - Blavier 1856-1858

1 J 1845 - 1 L 1855

- 1 B 1856

These 3 inspectors

will share a period of 15 years of inspection, during which the

works will be concentrated on the consolidations located under the

Montparnasse cemetery. Slabs with their initials can also be found

to the south, near the Voie verte and the Arcueil Aqueduct.

Juncker, for his part, will start with Mr. De Fourcy the first

drafts of the quarries atlas, presented at the universal

exposition in 1855. His successors will afterward dutifully go on

working on these drafts.

De Hennezel 1858-1865 - du

Souich 1865-1866

1 H 1860 - 1 S 1865

The decade preceding

the 1870 war will be a quiet period for the IGC and will give the

opportunity to normalize all the different systems used until

then. The works will be more modest and less numerous, but

counting with consolidations done in the 15th arrondissement and

under the Rue Broussais.

de Fourcy 1866-1870

1 F 1868

Eugène de Fourcy will,

for the short duration of his inspectorate, resume the golden

age of the IGC; he will notably participate in the consolidation

works under the Montparnasse cemetery and of the foundations of

the Montsouris reservoir. De Fourçy will also be the supervisor of

the

[quarries Atlas], still used today in its modern form: the IGC

maps.

Jacquot 1870-1872

1 EJ 1870

André Eugène Jacquot

certainly had the most arduous inspectorate, in the middle of

the 1870 war and later during the Paris Commune. During this

period, the IGC will suspend its activity, go away from Paris and

finally Jacquot will be ordered to cease completely its

activities, and surrender all the underground carries maps drawn

by his predecessors

to the representatives of the insurectionnal

government of the Commune.

- Lantillon -

-

Named quarries

"inspector", this Communard will not

exercise any title in the

service. His only decision will be the transferring of all the

quarries archives to the Hotel de ville (town

hall), which will be

set to fire the same year, causing the loss of a century's worth

of documentation on the underground.

Descottes 1872-1875 -

Tournaire 1875-1878 - Gentil 1878-1879 -

Roger 1879-1885

1 D 1874 - 1 T

1876 - 1 G 1879 - 1 R 1880

These four inspectors

will work for 15 years on the service reconstruction, and also on

the reconstitution of the quarries Atlas, which will be done with

the help of De Fourçy. They will do lots of work in the south of

Paris, essentially bourrages of search galleries.

Roger will also

work in the 15th arrondissement and under Montsouris where some of

his classification slabs can be found.

Keller 1885-1896

1 K 1886

Keller will take care

of various works in the Sarrette quarter and will distinguish

himself with the consolidation of the Montsouris reservoir. He

will probably be one of the last inspectors of the quarries'

golden age that will end at the beginning of the 20th century and

whose consolidation slabs, tidily cut then blackened, will

progressively be replaced by enamelled slabs or numbers hastily

painted.

Wickersheimer 1896-1907 - Weiss

1907-1909

554 W 1899

For the last two

inspectors having the same initials, their respective works can

only be distinguished by the year of their making. During his

inspectorate, Paul Weiss will start a friendship with someone

named "Emile

Gerards",

sub-inspector of the Travaux de Paris and a quarry enthusiast who

will become the author of the

encyclopaedic piece of work:

Paris Souterrain

(Paris underground)

|

The

Paris Catacombs

From cemeteries...

to the quarries of Paris

|

|

Since

the origin of the Paris city and until the Revolution, all

parisians were buried in various cemeteries. initially located

around the city, according to an ancient roman law. Century

after century, the increase of the city's size will

progressively absorb its suburbs, with the result that in 1789

the 200 cemeteries in Paris, depending from as many churches,

aren't sufficient anymore to contain the remains of all these

former Paris inhabitants. Victims of the black plague,

epidemics, starvations, of all the wars since the middle age

are resting there, dropped in the cemetaries, piled up on

several levels in the mass graves of the churches. Each day,

new cadavers join the previous ones. Churches and cemetaries

are vast, muddy fields where beggars, salesman, acrobats and

prostitutes rub shoulders with each others.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Trenches

are dug, dead bodies are left behind the precinct walls, and

everyday risks of an epidemy in the city are greater. Paris is

flooded by its dead, the odour is unbearable, even the bread and

water are contaminated by putrefaction and all reports on

public health safety are alarming. Citizens complain, incidents

and infections are frequent, and cemeteries continue to be

filled a bit more without anything else happening. Reports pile

up; the first ones date back from 1554 and are already ominous.

The medicine faculty of Paris and doctors from the royal

science academy in 1737 only validate these declarations. For

the sole Cimetière des Innocents, an estimate of 80000 cadavers

were added during the last 30 years of the monarchy.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

The

architecture of this old church shows in cross-section the

various additions that year after year transformed this place

of worship into a crypt intended to the monks, then into a

burial ground, reserved to the rich ones trying to bring the

divine mercy on them by laying by their side.

Then

come the Bourgeois who, lacking available space in the

church itself will generously pay to be buried in the

improvised cemeteries. Courtyards, fields located around the

church expand and flourish with graves. Then additional floors

niches, arches will need to be built, mass graves will need to

be dug out to satisfy the people, from the richest to the

poorest, unable to conceive being buried somewhere else than

close to God after their death, notwithstanding any

consideration for the living. On the alcoves' walls bordering

the courtyard of the Saints Innocents cemetery, representations

of dances macabres (dances of death), pagan images of dead and

living dancing, figuring together the daily

reality of

Parisians. (See annexes)

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The

walls in the cellar of a restaurant owner located

Rue de la lingerie, (at

the actual level

of

- Les Halles-)

) right next to the Innocents cemetery will break down

the 30th of May 1780. The

discovery of what will pour into the building's cellar will

cause an unutterable horror: cubic meters of old bones mixed

with decomposing cadavers, entangled putrefied mortal remains

made the wall give way under their weight. The building is

completely contaminated, walls are oozing and it is said that

just days after putting his hand on the wall, a mason will

catch gangrene. The same happens with the surrounding houses

and streets; this cemetery, like all the others in Paris, is a

big mass grave located a few meters from apartment buildings,

literally placed side-by-side with the cemeteries.

|

| |

|

|

|

|

Following

this incident, parliament will make a decree on the 4th of

September, 1780 to close the Innocents cemetery. For the following

5 years this decision will have no other effect than accumulate

more bodies in the surrounding cemeteries. The power in place

appears to stay completely helpless against this insolvable

problem.

The

"solution" will come from police lieutenant Lenoir who for several

years has offered to transfer the bones to the old underground

quarries. The idea will finally be endorsed by a ruling from the

state council. The first quarries inspector will be notified and

the Cimetière des Innocents will be disused; the bones will be

transferred to the hamlet called the

Tombe Issoire*, between the

Barrière d'Enfer and the Petit Montrouge.

This is how

the history of the capital city's cemeteries and that of the Paris

quarries will meet to become the

Paris catacombs. |

| |

|

|

|

|

Convoys of

black-draped chariots will form each evening funeral processions

accompanied by priests and dirges, and will pass through Paris to

transfer the mortal remains gathered over the centuries. Thusly,

from cemetery to cemetery, these processions will repeat again and

again, from 1785 until 1814. After a few years they will lose

their sanctity to first become a curiosity then a mere routine.

Bones will be poured into wells, shovelled and displaced on wooden

carts then heaped up and classified by genre to end up piled up

and put in order.

The

Viscount of Thury, quarries general inspector from 1808 until 1831

will be in charge of imagining the arrangements worthy of giving

the remains a well deserved rest. He will give these anonymous

residents a dark and gloomy decorum, with philosophical citations

related to death and remembrance. Tablets will indicate the

cemetery of origin and the repository date.

Many

illustrious figures will be found there pell-mell: Rabelais,

Mansart, Charles Perrault, Jean Baptiste Lully, Danton,

Robespierre, Colbert, Molière and hundreds of other celebrities,

like Hericart de Thury and Guillaumot themselves, great architects

of the catacombs who in their turn will find there their last

abode.

More than 6

millions Parisians will so be transferred into what will become

the biggest necropolis in the world. |

Annexes:

The full story

of the Cimetière des Innocents

can be consulted [here]

(in french)

A study of the

dances of death

painted on the church's alcoves is detailed [here]

(in french)

*

Tombe Isoire, later

renamed Tombe Issoire: the name supposedly originates from a giant buried under

the Montsouris plain. Depending on the versions: a saracen in the times of

Charlemagne, or a bandit named Isouard or Isoré who would have given the name of

"Tombisoire", meaning "assembling of tombs" in the middle-age.

First visit of

the Catacombs

|

Before going down into the dark underpasses

of the city, one must take the time to recall the remembrance of

the first visits that have been enthralling the Parisians for

almost 2 centuries. The passion for this curiosity starts without

a doubt with the transfer of the cemeteries' burial places before

the eyes of dumbfounded inhabitants. At the beginning of the 19th

century, solicitations will be sent to the catacombs management,

to the quarries service or directly to Monsieur de Thury to ask

for an authorization. Curiosity cabinets, showing samples of rocks

discovered in the quarries, are visited from 1815 by a few

scientists, researchers or naturalists, but the catacombs also

were visited by some renowned guests: Charles X in 1787, the

emperor of Austria François the 1st, on 16 of may 1814. Some very

rare writings dating from this time and left on the walls by these

mundane visitors, countesses or notables can still be found. In

1830 these few privileged ones stroll almost freely into the

underground tunnels, more or less guided by representatives of the

administration. Some visitors get lost, and bones robbery as well

as damages are noted, which leads to the adjournment of the visits

from 1833 until 1874. Only the highest personages still have the

right to receive rare "invitations": Napoleon III in 1860, Oscar

II of Sweden and the chancellor Bismarck in 1867. Then the 1870

war against Prussia will start, during which the Paris Commune

will fight fierce combats in these underpasses. |

|

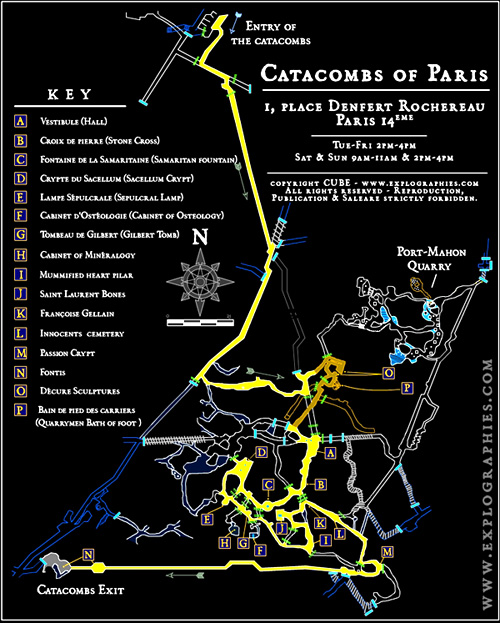

In 1874 it is decided to re-open the "Ossuaire

Général de Paris" (General

Ossuary of Paris) every first and third Saturday of each month.

the visit follows more or less this "catacombs way", traced with a

smoke line on the quarry ceiling depending of the fancy of the

administration staff across all the underground network, going

down the Rue Saint Jacques,

the Arcueil aqueduct, and passing of course

through the geological and osteological cabinets. Visitors

discover Port Mahon, sculptures from Décure and the quarrymen

footbath... Everyone hurries up then to enter the catacombs

through the Barrière d'Enfer

courtyard, provided with an official authorization... and a

candle. Then a real frenzy takes hold of the visitors who

sometimes will go inside without guides, candles or

authorization... on the 2nd of April 1897 and unauthorized concert

organized in the catacombs will make a great to-do. |

|

About a hundred guests will receive a

mysterious invitation, asking them to present themselves in front

of the catacombs entrance on a given day, advising them not to